Programming on Both Sides of Your Brain¶

A lot of disagreements in software engineering seem to have a deeper background than mere technical considerations. Should you move fast and break things, or should you reinvent the wheel? Does it matter how the code looks like when it does what you want? And what is the purpose of it all in the first place? I propose that many of those arguments arise from different people using different of two possible fixed worldviews in a variety of contexts, which they assign automatically and mostly unconsciously, in a similar way to how our brain resolves bistable perceptions. Furthermore, I propose that the ability to consciously switch between the two worldviews, and the experience needed to decide which one to use in the given context, are crucial for the work of a software engineer.

Necker Cube¶

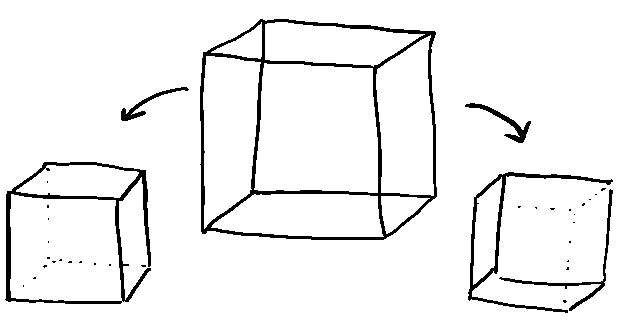

Probably the most well known example of bistable perception is the Necker Cube: a two-dimensional wireframe drawing of a cube, which can be interpreted in two ways, because it lacks any cues about the depth of the parts of the image.

When we look at the drawing, we automatically pick one of the possible interpretations, and it becomes obvious to us that it’s the correct one. It requires a conscious effort to switch to the other interpretation, and some people can’t do it at all. The initial choice is based on context cues, such as lighting and position of the drawing, personal preference, cultural biases, and possibly some amount of randomness.

There are other examples of bistable (and multistable) perceptions, some even harder to switch between without training. But I think this one illustrates the mechanism well enough for our purposes.

Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain¶

In 1979 Betty Edwards published a book describing her technique for teaching drawing. Her idea was based on the theory of how left and right brain hemispheres are responsible for different ways of perceiving reality, that was popular at the time. Today we know that the processes responsible for those two ways are not actually confined to their corresponding hemispheres, but rather are both whole-brain processes, but the terminology stuck, so you can still read people referring to the more verbal and analytic way as the left-brain functions, or L-mode, and the more visual and intuitive way as the right-brain functions, or R-mode (the hemisphere sides are reversed compared to which sides of the body they control, because the nerves cross: left hemisphere controls the right side of the body, and vice versa). This supposedly explains why left-handed people are more creative, having a more dominant right hemisphere.

In any case, no matter how that relates to the actual positions of parts of our brains, and the processes that take place, the technique seems to be working: by intentionally suppressing the understanding of the different parts of the scene we can shift our perceptions to seeing how it looks like, so to say, instead of what it is, and make it easier to re-create the looks on the paper. Whatever the neurological explanation for it, the trick seems to be working for many people.

You might find that this general strategy may work in other areas than drawing as well. For example, when listening to music, when tasting food and drinks, or even with more abstract things, like interpreting poetry, or understanding mathematical proofs. It often feels like switching between focusing on details, and perceiving the general shape and feel.

I think that we often automatically pick the right mode of perception for the task in similar way to how we pick an interpretation of the Necker cube above, based on context cues, personal preference, cultural biases, and experience. And since it’s mostly unconscious, we are often not aware that a choice has been made, and that a different interpretation is possible, unless we intentionally expend the effort to consider it. And that becomes easier with practice.

Phases of Software Design and Development¶

If you ever tried to design a user interface while at the same time writing code for the back-end, you might have noticed that it’s very difficult to make it work the way the users expect, instead of mirroring the internal representation. This is why those tasks are often separated, performed at different times, if not by completely different members of the team, or even different teams. There can be many more such phases, where you need to focus on different aspects of the product, consider different trade-offs, and focus on different levels of abstraction.

I believe this is, at least partially, because those tasks are best solved in different perception modes, and we can only be in one of those modes at a time, just like we can only see one interpretation of the Necker cube at once.

And while there may be a big variety of roles and phases, depending on the organization and methodology and the task at hand, you might notice that the worst disagreements usually happen between pairs of roles that can be roughly divided into two families, roughly corresponding to the L-mode and R-mode from Betty Edwards’ book.

Programming on the Left Side of the Brain¶

The L-mode generally sounds like your stereotypical science nerd. You write code because you enjoy the difficulty of doing it. You care about the correctness of your solution not because it will have some business purpose, but because an incorrect solution would be wrong. You want your code to be good, whatever it means in the context. You know that either something is true, or it isn’t, and the only way to tell is through contact with the harsh reality. You trust your co-workers, and cooperate without friction, unless someone breaks that trust repeatedly – then you simply start avoiding that person and working around them. You very carefully pick your tools and dependencies, and you like to understand how they work before you use them. You don’t like overcomplicated libraries that do much more than you need. If you see something that isn’t right, you will try to fix it yourself, and if that is not possible, you will avoid using it. You believe position should be earned through work, and trust should be earned trough repeated interactions. You don’t care much about authorities, and you don’t believe something is right just because someone says so. You tend to avoid taking sides, and you just want things to work. You prefer to just show things over describing them. You are generally quiet, and you prefer to results speak for you. You are generally an optimist, and you believe in improving things for everyone.

Programming on the Right Side of the Brain¶

The R-mode is more like a salesman. You don’t really care about how the thing is done, as long as everyone agrees that it works. If someone disagrees, you may fix it by changing how it works, or by convincing that person that they are wrong, either way is fine, as long as there is a consensus. People who believe in inviolate truths just don’t have a flexible mind. You love workarounds and temporary solutions. You juggle technical debt like a government economist. You take sides and stick to them, because position and trust is achieved through loyalty or authority enforcement. You like procedures and processes, even if they don’t work – after all it’s not your fault it doesn’t work when you followed the process correctly. You have friends and enemies among your co-workers, but it changes all the time, depending on what you need and who has what to offer. You love powerful and complicated tools and libraries, especially when they are popular – after all, nobody was fired for choosing IBM. You are sensitive to fashions and trends, and you always try to work on the coolest projects. Your favorite mode of communication is telling stories. You are generally a fatalist, and you believe in making the best use of what is available to you right now.

Switching Contexts¶

The above descriptions are very stereotypical. In reality, to survive in the modern world, everyone one of us, even the most nerdy nerds and the most popular celebrities, have to switch between those modes. Doing grocery shopping? You need the L-mode. Deciding what to have for lunch? That’s R-mode. And we often don’t even realize we switch those modes, because it happens mostly automatically, depending on the context. Unless sometimes it doesn’t, and we are stuck in the wrong mode for the task at hand. This can happen for a variety of reasons.

Some people simply prefer one mode over the other, because of their personality, neural makeup, or cultural biases. For example, autistic people generally tend to prefer the L-mode, while people with authoritarian personality traits will lean towards the R-mode more.

Your training and experience might tell you that a certain mode works better in the given situation, while someone who was trained for a different profession, or even just by different methodology, will disagree with you, not only about what mode is more appropriate, but even what the situation actually is.

You might have locked on to a specific mode at a certain time in the project, and in the mean time the situation may have changed, so a person joining later will choose a different one. Or you might have noticed the change and switched your mode, while your colleagues didn’t.

Finally, if the task at hand is novel, you might simply not know which mode to choose, and may pick it at random.

Whatever the cause, when two people are in different modes in the same context it’s very difficult for them to agree about anything. And since the mode switching is normally completely unconscious and automatic, and because the mode you are in always feels the only obvious one for the situation, it feels like a perfectly normal, smart and reasonable person suddenly disagrees with you about the most fundamental and common sense things. It’s very frustrating.

Of course even when you realize that you have a mode mismatch, it’s not trivial to decide which mode is more appropriate for the given context, or even where the boundaries at which it should be switched lie. Whichever mode you are at the moment, it feels like the obviously right one for you, and since they differ in how values are assessed, it may be hard to decide which one was more appropriate even in hindsight.

Elasticity and Training¶

It turns out that people who can switch between the two modes easily are generally more successful at software engineering jobs (and many others too). Obviously it’s not enough to be able to switch, but also to know when to do it, and that comes with experience, but if you generally are reluctant to switch, you are more likely to be in the wrong mode at the wrong time.

Having the right training for the job helps with the experience part. And that is often hands-on training, and not theoretical knowledge read in a book, because the context picking and mode switching is mostly automatic, based on unconsciously picked cues, that a book would not communicate.

Dividing the project into phases and the team into roles at the right places helps with switching to the right modes as well, by making the boundaries of the different context explicitly visible, so a conscious effort can be made by the team members to get into the right mode for the particular phase and their role in it.

Due to the different roles often requiring different modes, there is no way to completely avoid conflict inside the team. This is in fact the main reason to have the roles in the first place – to catch problems visible in either of the modes. It’s important to realize that those differences are often irreconcilable – the differences between how the world is seen in the two modes makes it impossible to form a consensus, and some other way of conflict resolution is necessary. In the end it might be just necessary to agree to disagree. For this reason it’s important for the different phases and roles to have distinct, non-overlapping areas of responsibility, so that in the case of irreconcilable disagreement it is known whose decision is final.

Conclusion¶

While my hypothesis of the two distinct mental modes in software engineering work is completely made up and unsubstantiated, and based entirely on anecdotal evidence, I am confident that it provides a useful tool for understanding the behavior of teams, and may help in organizing projects in a way that reduces conflict and improves performance. I have absolutely no proof of that beyond my feelings about this. The reader is advised to use their own judgement.

dopieralski.pl

dopieralski.pl